Vol 121: Times I couldn’t swallow

Every day, I stand in front of my patients while they sit on an examination chair. But as a child, and over the years as an adult, I’ve also spent moments sitting on one of those chairs as a patient, seeing and experiencing a doctor’s visit from the other side. Not as the one aiming to cure or alleviate suffering, but as the one being treated, hoping for cure or alleviation. I suspect my great health has been buoyed by my commitment to regular exercise and a healthy diet. Over the years, however, that health has sometimes been mired by a plague of recurrent tonsilitis where the tonsils in my throat would swell like a balloon making it hard for me to swallow.

In my last column, I told the story of my friend, a renowned foot and ankle surgeon in the US who sustained an ankle fracture and had to undergo surgical intervention. It was a reminder to us all, and particularly him, that the healer is not immune to frailty. In keeping with that philosophy, I wanted to share my experience of being a patient and the lessons it’s taught me.

As a reminder, the tonsils are a set of two round lymphoid masses of tissue filled with white blood cells. They sit at the back of the throat (pharynx) and function as part of the immune system, protecting the body from infection. Because of their strategic location, they help block bacteria from entering the body through the nose and mouth as the white blood cells target bacteria and kill them.

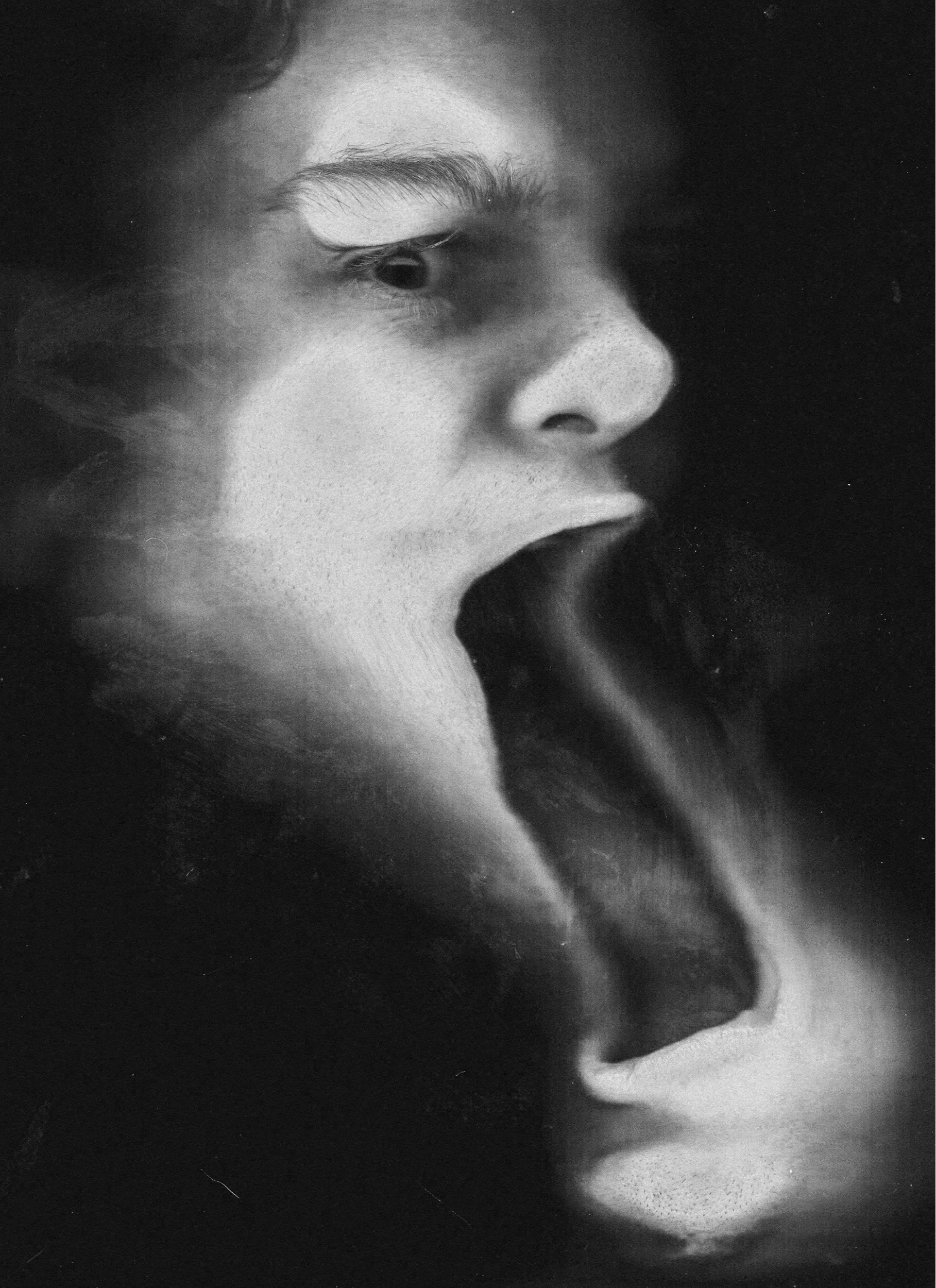

At times, via a cascade of internal events that I can rarely predict, those very same defense weapons malfunction and wreak havoc on my throat. Nights for me were always the worst. I could sense an oncoming attack as soon as I laid down. Just as my head hit the pillow, I knew this would be one of those nights I’d struggle to sleep as my tonsils took over. I could feel my throat tighten; my swollen tonsils like boulders eclipsing the tunnel of my throat. Swallowing my own saliva created a sharp burn as if I were ingesting crushed glass.

So, I tried not to swallow or speak as I slowly and deliberately struggled to breathe. My swollen tonsils no longer only blocked pathogens and food, they also made it harder for oxygen to enter my body. The deep rasp it created every night as I fought to sleep is forever ingrained in my subconscious. I still vividly recall my mom wiping the sweat off my forehead and checking often to see if I had a temperature. I always did. Her concern grew exponentially as my appetite faded and I spent more and more time in bed.

My bouts would typically last upwards of a week, sometimes longer depending on how quickly I sought medical attention. I don’t recall when it started but I know that by the age of ten, I knew the first and last names of my family physician (Dr. Gloria Sands) and ENT specialist (Dr. Charles Johnson). They were my heroes and stood guard for many years, helping me through every flare up and I couldn’t be more grateful. Antibiotics, oral anti-inflammatories, salt-water gargles, honey-lemon lozenges and prayers. I can’t help but wonder if the time I spent in their offices carved a permanent desire within me to relieve pain in others who are suffering.

In one particularly bad episode, my tonsils were so enlarged my father considered taking me to the hospital but I begged him not to. I cried uninterrupted believing in my adolescent brain a hospital was the place where people went to die. So, as much as it pained me, I forced myself to eat to prove I was getting better. I don’t remember what I ate but I remember the pain it caused. Even chewing required a herculean effort with steady, wincing pauses. Swallowing was the worst part, eliciting pain that I dared not express. Every gulp felt like hot lava cutting its way through my neck. By morning, my condition had worsened. Beyond the intense throat pain and difficulty swallowing, breathing was a challenge, my ear was sore to light touch, my eyes were sensitive to light and my head pounded over and over.

By the time I saw Dr. Johnson, my neck was so swollen that he could barely unclench my jaw to examine me. My tonsils were hypertrophied to double their typical size. There was obvious nasal turbinate swelling and my eyes were constantly watery. After years of dealing with this, it was the first time that he mentioned that I should have my tonsils permanently removed. Fortunately, after an extended course of oral antibiotics, an anti-septic mouth rinse and a higher dosage of oral anti-inflammatories, I recovered without further incident.

It would be years for me to determine that the causative factor for my recurrent infections was a persistent post nasal drip from seasonal allergies. Fortunately, as I’ve gotten older my rate of recurrence has lessened as does the need for any invasive surgical treatment. Knowing the cause has helped tremendously. My flare ups now occur zero to once a year. Tonsillectomy offers a path to full recovery but for various reasons, it’s a path that I’ve always been reluctant to take. Meanwhile, I know others who’ve had their tonsils removed and would do it again without hesitation.

Truth be told, there was an upside to my childhood infections. Just staying home from school was enough to make me giddy. But the endless supply of popsicle and ice cream, reserved for only me, quickly and magically satiated my grief and masked every turmoil I’d ever known. During some of my milder flare ups, there were times I felt like Charlie in Willy Wonka’s factory. I stuffed one scoop of ice cream into my mouth after the next, chewed on lozenges like candy and used the empty popsicle sticks to sing as I moon-walked around the bedroom with my older brother.

The lessons this taught me are that even when seemingly minor parts of the body malfunction, it can yield significant consequences. I also learned that illness isn’t just physical, its emotional, exhausting and lonely which is why relief can be so transformative. I remember exactly how it feels to simply swallow again without pain. There’s a palpable comfort in the return of such small ordinary mercies that reminds me to never overlook the quiet suffering that hides behind common complaints.

Ultimately it also taught me that even when bad things happen, with time things eventually get better. And not because time is a cure but because it allows the scars that diseases inflict on our memory to soften. The fact that the few times I spent dancing with popsicle sticks are more powerful than the numerous times I spent curled in pain, fighting to swallow, are proof of that.

As a child who always wanted to be a doctor, my silenced voice was humbled into understanding and empathy for all patients. So, today when I treat patients, I do so with sharpened awareness that fragility is a constant companion for all humans and we are constantly just one accident or incident away from death or disability. That knowledge is tempered not just by medical expertise and clinical experience but by empathy born of a lived illness and the devastating loss of too many loved ones.

When you swallow, a delicate and sophisticated choreography ensues where food is mixed with saliva to form a bolus. The tongue then pushes that bolus to the back of the mouth against the hard palate. The soft palate elevates to close access to the nasal cavity, the larynx elevates and the epiglottis moves down to protect the airway. The pharyngeal muscles contract and push the bolus down toward the esophagus and further contractions push food down into the stomach.

When the tonsils are inflamed, that process is broken and health is quickly compromised. So today, when I think of the times I couldn’t swallow, I’m reminded of my own frailty, the never-ending beauty of medicine and my unyielding gratitude for those who administer it with care and compassion.

This is The KDK Report.